The output of a manager is the output of the organizational units under his or her supervision or influence. This book talks about how to increase the managerial output.

Managerial Leverage

Managerial output = Output of organization = A1 * L1 + A2 * L2 + … where A is a managerial activity and L is the corresponding leverage. Manager activities include information-gathering, information-giving, decision-making, nudging, and being a role model. Leverage, by definition, is the measure of the output generated by any given managerial activity. Based on the formula, a manager can increase his output by:

- Increase the rate with which a manager performs his activities, speeding up his work.

- Increasing the leverage associated with the various managerial activities.

- Shifting the mix of a manager’s activities from those with lower to those with higher leverage.

The art of management lies in the capacity to select from the many activities of seemingly comparable significance the one or two or three that provide leverage well beyond the others and concentrate on them. This is how we should allocate our time —— the single most important resource that we allocate from one day to the next. Given time is a finite resource, and when we say “yes” to one thing we are inevitably saying “no” to another, we should be very selective about things we choose to do.

Meetings —— The Medium of Managerial Work

There are two kinds of meetings. The first is process-oriented meeting, knowledge is shared and information is exchanged. Such meetings take place on a regularly scheduled basis. The second is mission-oriented meeting, the purpose is to solve a specific problem and produce a decision. They are ad hoc affairs, not scheduled long in advance, because they usually can’t be.

One-on-one is a process-oriented meeting. It should be regarded as the subordinate’s meeting, with its agenda and tone set by him.

For a mission-oriented meeting, the purpose should be decided beforehand and it’s the meeting chairman’s job to make sure the meeting accomplishs the purpose for which it was called. Since the goal of this type of meetings is to make a decision, we should control the number of attendees. A decision-making meeting is hard to keep moving if more than six or seven people attend. Eight people should be the absolute cutoff. Decision-making is not a spectator sport, because onlookers get in the way of what needs to be done. Once the meeting is over, the chairman must nail down exactly what happened by sending out minutes that summarize the discussion that occurred, the decision made, and the actions to be taken. And it’s very important that attendees get the minutes quickly, before they forget what happened. The minutes should also be as clear and as specific as possible, telling the reader what is to be done, who is to do it, and when.

Decisions, Decisions

An organization does not live by its members agreeing with one another at all times about everything. It lives instead by people committing to support the decisions and the moves of the business.

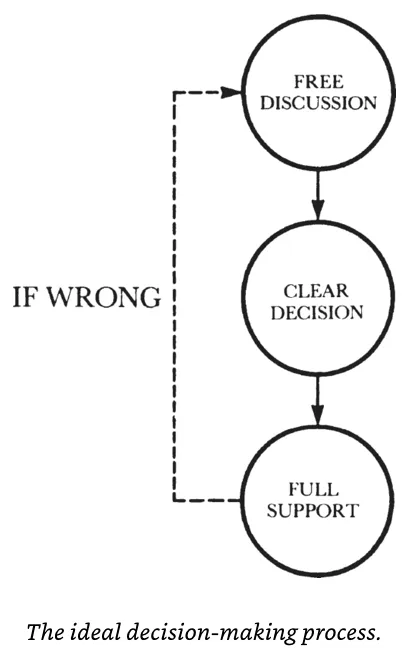

The ideal decision-making process involves three stages. The first stage should be free discussion, in which all points of view and all aspects of an issue are openly welcomed and debated. The greater the disagreement and controversy, the more important becomes the word free. The next stage is reaching a clear decision. Again, the greater the disagreement about the issue, the more important becomes the word clear. Finally, everyone involved must give the decision reached by the group full support.

The person makes the decision is the DRI and everyone else needs to disagree and commit once the decision is made. The DRI should have the confidence to make the decision especially when consensus is not reached and the self-confidence mostly comes from a gut-level realization that nobody has ever died from making a wrong business decision, or taking inappropriate action, or being overruled (most decisions are two-way doors).

We shouldn’t enter the decision-making stage too early or wait too long. If we make the decision too early, we may miss some opinions. If we make the decision too late (aiming for the absolutely right decision), we are not moving fast enough. Often, it’s better to try out a 60-point decision and iterate on it quickly based on feedbacks than trying to find a 100-point decision endlessly.

For decision-making, one of the manager’s key tasks is to settle six important questions in advance:

- What decision needs to be made?

- When does it have to be made?

- Who will decide?

- Who will need to be consulted prior to making the decision?

- Who will ratify or veto the decision?

- Who will need to be informed of the decision?

Planning: Today’s Actions for Tomorrow’s Output

Planning is to answer the qeustion: What do I have to do today to solve —— or better, avoid —— tomorrow’s problem? Today’s gap represents a failure of planning sometime in the past.

MBO (management-by-objectives) is a planning process that can be applied to daily work. A successful MBO system needs only to answer two questions:

- Where do I want to go? (The answer provides the objective).

- How will I pace myself to see if I am getting there? (The answer gives us milestones, or key results.)

The Sports Analogy

The role of the manager is that of the coach. First, an ideal coach takes no personal credit for the success of his team, and because of that his players trust him. Second, he is tough on his team. By being critical, he tries to get the best performance his team members can provide. Third, a good coach was likely a good player himself at one time. And having played the game well, he also understands it well.

Performance Appraisal: Manager as Judge and Jury

Performance reviews is the single most important form of task-relevant feedback we as supervisors can provide. The goal is to improve the subordinate’s performance instead of cleansing our system of all the truths we may have observed about the subordinate so less may very well be more (give one feedback and one area for improvement at a time).

It might be counterintuitive but we should spend more time trying to improve the performance of our stars. After all, these people account for a disproportionately large share of the work in any organization. Put another way, concentrating on the stars is a high-leverage activity: if they get better, the impact on group output is very great indeed. We must keep in mind, however, that no matter how stellar a person’s performance level is, there is always room for improvement.